Diagnosis and Staging

Initial Diagnosis – finding out you have cancer

About half of kidney tumors are found during a CT scan or X-ray. Some kidney cancers are found after certain symptoms lead to testing. Other kidney cancers are found by chance, while the doctor is looking for something else.

Testing for a Kidney Cancer Diagnosis

Doctors can do different tests to find out how much cancer is in your body. These tests can also help you and your doctor create your treatment plan. Your primary care doctor may have already done some of these tests for your initial diagnosis. However, a kidney cancer specialist may need to redo some or all of these tests.

If you have a kidney tumor, a kidney cancer specialist or team of specialists will do tests to find out:

- The size of the tumor

- If the tumor is cancerous

- If any cancer cells have spread to other parts of your body

- What treatment options are available

Tests or exams may include:

Physical exam to check your overall health

This could include checking vital signs like:

- Blood pressure

- Temperature

- Weight

- Pulse (heart beats)

Complete medical and family history

Your healthcare team will ask you about medicines you take, any other health conditions, and results of your health tests. They will want to know if any family members have had kidney cancer or other diseases.

Blood tests

Your team will take samples of your blood to check how well your kidneys are working and your overall health. Some blood tests include:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) test – this measures the number of cells in the blood such as red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- Blood chemistry tests – these look at how well your liver and kidneys are working, and electrolytes like sodium and potassium.

Urinalysis

A test of your urine (pee) that looks for blood, extra proteins, or infection

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan

An imaging test that uses X-rays to create detailed images of certain areas of your body. It helps doctors find cancer. They will scan your abdomen (belly) and pelvis to show your kidneys and nearby areas to see if the cancer has spread.

- Before your scan, you may get contrast (a substance that you take by mouth or get injected into a vein) to improve the quality of the imaging pictures. Tell your doctor if you’ve had any reaction to contrast or iodine in the past

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

An imaging test that uses radio waves and powerful magnets to take pictures of your body. An MRI is used to check if kidney cancer has spread to major blood vessels or the brain.

- During an MRI you will need to lie still in an enclosed space for 15 – 90 minutes. Before your doctor schedules an MRI, tell them if you’re anxious about being in an enclosed space. They may have options to make you more comfortable during the MRI.

- If you have metal in your body, such as a hip replacement or pacemaker, let your doctor know.

Bone scan

An imaging test that can show if the cancer has spread to your bones.

- Before the scan, a small amount of radioactive material is injected into a vein. It takes about 3 hours for the material to enter your blood. Doctors use a special camera to take pictures of the material in your bones.

Chest x-ray

An imaging test to see if the cancer has spread to your lungs. If something shows on the X-ray, your doctor may order a CT scan of your chest for a better look.

Biopsy

A procedure where a doctor removes a small sample of your tumor with a needle. Your team examines the sample to see if it is cancerous.

- A doctor (a urologist, surgeon, interventional radiologist, or another doctor) will insert a long thin needle through your skin into the tumor and remove a small sample.

- A pathologist at a lab will look at the tissue under a microscope to see what the cells look like and make a diagnosis.

- If the cancer has spread, your team may biopsy a sample from other areas of your body.

Based on imaging test, some patients won’t have a biopsy and will go straight to surgery. Your doctor will decide what is the best way to determine if you have kidney cancer.

Watch presentations from experts to learn more:

Types of Kidney Tumors

Benign Kidney Tumors

Benign kidney tumors are not cancerous and will not spread to other parts of the body, but they can grow and cause problems. Doctors can use many of the same treatments (such as surgery or radiation) to treat benign kidney tumors that they use for cancerous kidney tumors.

Some of the most common benign tumor types are:

- Angiomyolipoma – This is the most common type of benign kidney tumor. It often affects women or people with tuberous sclerosis, a rare inherited condition. If the tumors aren’t causing symptoms, doctors and patients may try a “watch and wait” approach. However, if they cause problems (like pain or bleeding), doctors may need to remove them with surgery.

- Oncocytoma – This is an uncommon type of benign kidney tumor. They don’t spread, but they can grow and cause other problems that require surgery. They may be related to chromophobe RCC. If you’re diagnosed with oncocytoma, your healthcare team should check you for RCC.

Kidney Cysts

A kidney cyst is a fluid-filled sac in the kidney. Not all kidney cysts are cancer.

Simple kidney cysts are small, rarely cause problems, and usually don’t need to be treated. They tend to be more common as people age. In about 40% of people (4 in 10), doctors find kidney cysts when taking CT scans or X-rays of their kidneys for other reasons.

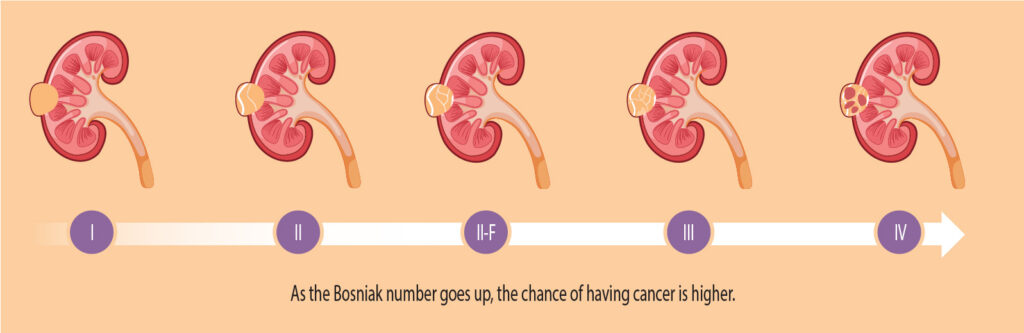

To find out if a cyst is cancer, doctors use the Bosniak classification system. This tells them if it needs to be removed, or if it can be left alone and watched. This system divides cysts into 5 categories, with Category 1 (I) as non-cancerous simple cysts that can be watched, and Category 4 (IV) as clearly cancerous cysts and should be removed. Doctors use CT and MRI scans to assign the Bosniak category.

Doctors often remove large or cancerous cysts with surgery.

Kidney Cancer

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC)

Renal cell carcinoma, also called renal cell cancer, is the most common type of kidney cancer. About 9 out of 10 kidney cancers are renal cell carcinomas.

RCC often starts as 1 tumor in a kidney, but sometimes can start as several tumors, or can be found in both kidneys at once.

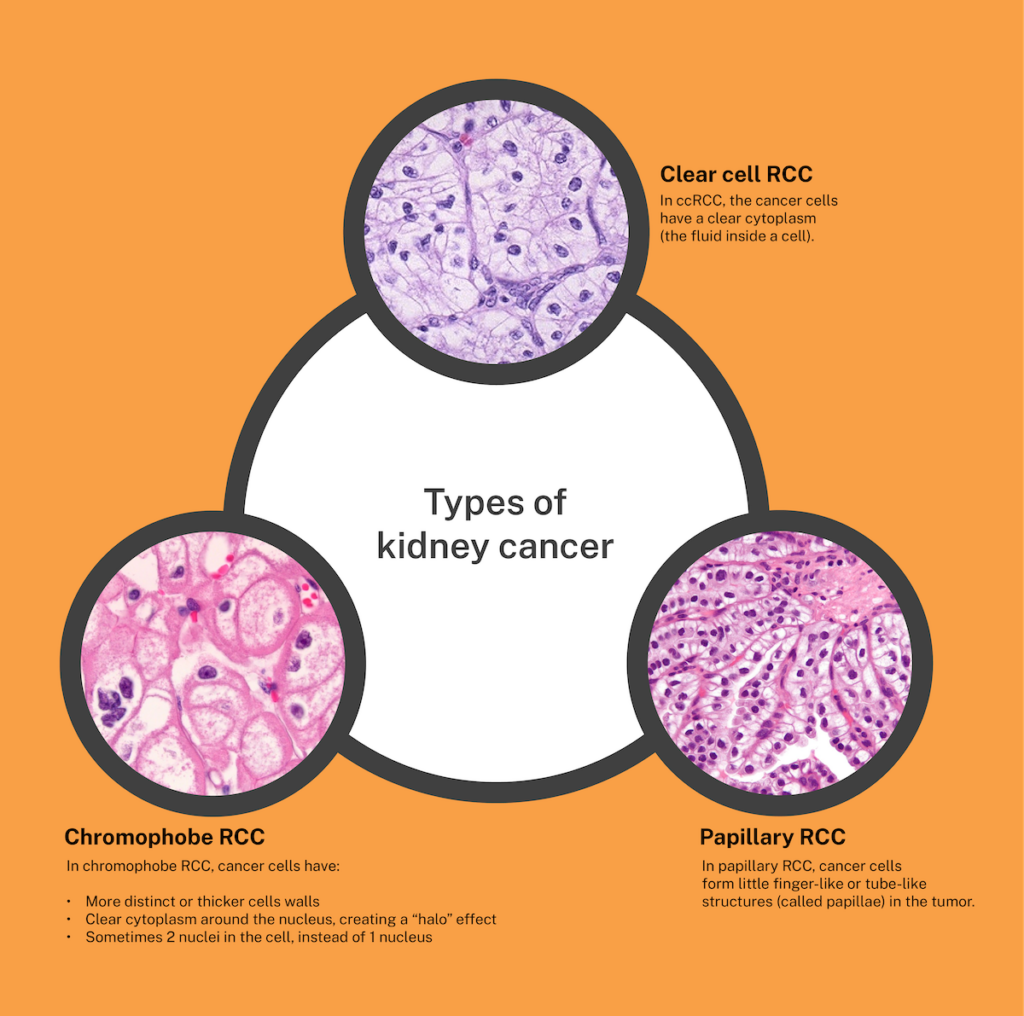

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC)

Clear cell RCC, or ccRCC, is the most common type of kidney cancer. About 70% of people with RCC (7 in 10) have this type of kidney cancer. It is called clear cell because the cells that make up this cancer look very pale or clear under a microscope. Clear cell RCC can be hereditary or non-hereditary.

Papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC)

Papillary RCC is the second most common type of kidney cancer. About 15% of RCCs (15 in 100) are this type. It is called papillary because it forms little finger-like projections (called papillae) in the tumor. Papillary RCC can be hereditary or non-hereditary.

Papillary RCC is the 2nd most common form of renal cell carcinoma. In specific populations such as those with African American ancestry the incidence may be high as 20-30% of kidney cancer cases. It generally presents at a lower stage and smaller size than other forms of kidney cancer such as clear cell. The prognosis may be better than some forms of renal cell carcinoma, but it still can act aggressively and spread to other sites.

Papillary RCC can affect individuals of any gender or race/ethnicity. Similar to clear cell RCC, papillary RCC has similar age of onset (median 64) and propensity for male gender (70%).

There is a slightly higher incidence of papillary RCC in those with African American ancestry. Individuals with chronic kidney disease may have a higher risk for papillary RCC for unclear reasons.

Papillary RCC may have specific genetic changes unique to this subtype not observed in other forms of kidney cancer. Mutations in genes such as MET, CDKN2A, NF2, and MLL3 are genes with recurrent mutations. Chromosomal changes common to papillary kidney cancer include gains in chromosome 7 and 17 and losses of chromosome 16 and Y.

Just like other forms of renal cell carcinoma, papillary RCC can metastasize to any organ. There may be slight differences in the distribution in metastatic spread though surveillance currently is not specific for disease histology. The most common sites of spread of papillary RCC include regional or distant lymph nodes, lungs, and the liver.

Due to the lower disease incidence, there have been less trials focused on papillary RCC so much of the experience treating the disease is observational. Consideration for clinical trials are recommended. The available agents studied in clear cell RCC have been used in papillary RCC, the positive response rate is frequently lower. Use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immunotherapy can be considered.

There are many ongoing research studies for papillary RCC, including work currently funded through the Kidney Cancer Association.

A special thanks to Dr. Brian Shuch at UCLA for providing additional information about Papillary RCC.

Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (chRCC)

Chromophobe RCC is a rare type of kidney cancer that makes up about 5% of all kidney cancers (5 in 100). It starts in the cells that line the small tubes in the kidney, which help filter waste from the blood. Chromophobe RCC can be hereditary or non-hereditary. It is less likely than other RCC types to spread to other areas of the body.

Chromophobe RCC gets its name because the cells look pale under the microscope. In Greek, chromo means “color” and phobos means “fear”, so chromophobe tumors “fear” the colored dyes that we use to stain cells. Clear cell kidney cancer also gets its name because the cells look pale or clear under the microscope. Despite this similarity under the microscope, the fundamental genetic and cellular pathways that cause chromophobe RCC appear to be completely different from those that cause clear cell RCC.

Individuals with two genetic diseases, Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) and Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome (BHD) can develop chromophobe RCC. TSC and BHD typically cause disease in other parts of the body, including the skin and the lung. However, most individuals who develop chromophobe RCC do NOT have TSC or BHD.

Beyond the genetic association with TSC and BHD, mentioned above, there are no specific risk factors that have been clearly established so far. It is quite possible that these risk factors exist but have not yet been studied.

Most chromophobe RCC tumors have very distinctive genetic changes, that are not seen in any other subtype of RCC. These genetic changes include 1) loss of one copy of six entire chromosomes (something that is seen in almost no other human cancer), 2) a high rate of mutations in genes encoded by the mitochondrial DNA that are essential for making ATP, the cellular fuel, and 3) a low rate of mutations in other genes, termed oncogenic drivers, that are found in most other tumors.

Chromophobe RCC metastases are most common in the lymph nodes, lung, liver, and bone.

Optimal treatment for metastatic chromophobe RCC is a rapidly emerging area of research. Some treatments that are effective for clear cell RCC also seem to work in some chromophobe RCC. Much more information is needed to understand why some tumors respond and others do not respond. It is also possible that specific targeted treatments may have greater efficacy in chromophobe RCC than in clear cell RCC. This is because the genetic and cellular features of chromophobe RCC are so different from those of clear cell RCC.

Research focused on chromophobe RCC is growing and evolving quickly! Clinical research (including clinical trials that include individuals with chromophobe RCC), translational research (including the identification of specific blood biomarkers and analyzing the cellular and pathologic features of metastatic chromophobe RCC), and laboratory-based research (including the development of optimized mouse models of chromophobe RCC and identifying and validating new therapeutic targets such as ferroptosis) are all moving forward at unprecedented rates.

A special thanks to Dr. Elizabeth Henske at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for providing additional information about Chromophobe RCC.

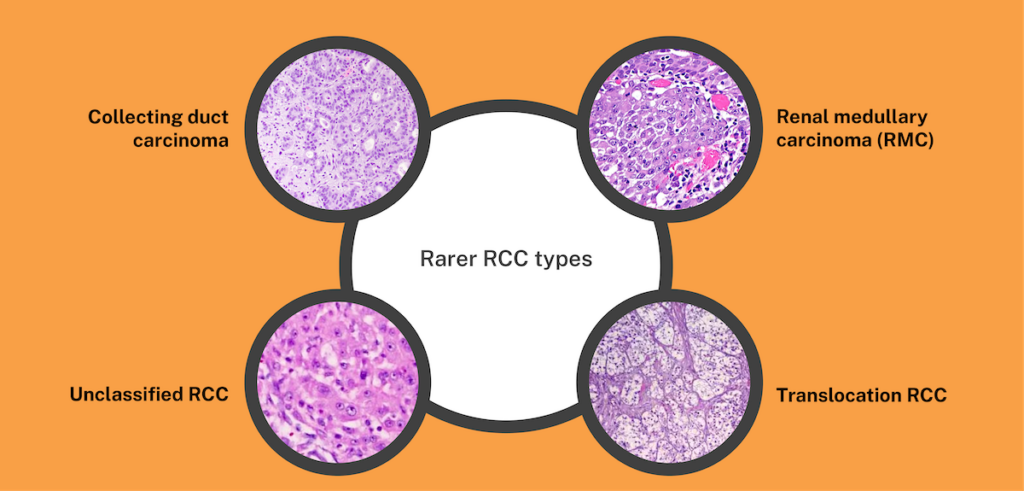

Rarer RCC subtypes

These types of RCC are very rare. Each make up less than 1% of RCC cancers (1 in 100):

- Collecting duct carcinoma – A very rare and aggressive type of RCC. When a person is first diagnosed, it is usually metastatic, meaning it has spread to other parts of the body. It is more common in younger people.

Collecting duct renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a very rare type of kidney cancer that occurs in less than 1% of all kidney cancers. Collecting duct tumors are different than other types of kidney cancers in that they are very aggressive and behave more similarly to bladder cancer.

Collecting duct tumors behave similarly to bladder cancer since both the bladder and collecting duct portion of the kidney share the same origin when the organs are formed in the body before birth. It is important that your cancer team works closely with expert pathologists who have experience in rare kidney cancers for accurate diagnosis.

Collecting duct RCC is frequently diagnosed in younger patients and Black patients as well as men.

Currently, there are no known risk factors for developing collecting duct RCC.

Due to the aggressive nature, collecting duct RCC can commonly spread to the lungs, liver, and bone.

The treatment of collecting duct RCC is largely different than clear cell RCC. Since the tumor behaves more similarly to bladder cancer, collecting duct tumors are treated similarly to bladder cancer with combination chemotherapy given IV. In contrast, clear cell RCC is typically treated with immunotherapy and/or pills (VEGF inhibitors) that block the formation of blood vessels that nourish cancer cells. However, there is some data that collecting duct RCC may also respond to VEGF inhibitors as well.

Since collecting duct RCC is a very rare cancer, we do not have a lot of data on what is the best treatment approach. Also, these tumors have not received a lot of research focus in the past. Clinical trials represent a wonderful opportunity to help find new and better therapies for patients with collecting duct RCC and other rare kidney cancers. Participation in clinical trials for patients with rare kidney cancers is highly recommended. You can find a clinical trial using the KCA’s Clinical Trial Finder.

A special thanks to Dr. Charles Nguyen at City of Hope for providing additional information about Collecting Duct RCC.

- Renal medullary carcinoma (RMC) – A rare and aggressive cancer that attacks the kidney. This cancer causes more deaths than other kidney cancers because it quickly spreads to other organs, often before it’s diagnosed. Less than 5% of patients (5 in 100) diagnosed with RMC will live beyond 3 years. This cancer is found almost always in young Black people with sickle cell trait.

Renal medullary carcinoma (RMC) is a kidney cancer that was first described in 1995. RMC grows very fast and behaves very differently from the other kidney cancer subtypes. In the original study, half of the people diagnosed lived less than four months. Today, treatments have improved, and people can live about 18 months on average while up to 10% may be cured. Researchers are still working on better treatments.

The patient population affected by RMC is different than the typical kidney cancer patient. RMC mostly affects young Black people who have sickle cell trait, sickle cell disease, or other blood conditions that cause red blood cells to become sickle-shaped. About 1 in 14 African Americans have sickle cell trait, and only 1 in every 20,000 to 1 in 39,000 of individuals with the sickle cell trait will develop RMC. Overall, about 300 million people around the world have sickle cell trait. The number of people with this trait can vary from 7% in African Americans, 23.5% in some parts of Greece, 10% in parts of Turkey, up to 13% in central India, 20% in eastern Saudi Arabia, and 10%-40% across equatorial Africa. Among the Baamba tribe in Uganda, it can be as high as 45%. Most reports of RMC come from the United States or Europe. This may be because doctors in other places do not always recognize RMC, or because there are certain environmental or regional factors that could increase RMC risk in the United States and Europe. It is more common in men than in women, and about 70% of these tumors start in the right kidney. RMC is the third most common type of kidney cancer in children and young adults. Around half of people with RMC are 28 years old or younger, with some as young as 9. It is less common for people to be 35 or older when they get RMC.

The red blood cells of people with sickle cell disease turn into a sickle shape all over the body, causing many health problems that are not related to RMC. But for people with sickle cell trait, their red blood cells only become sickle-shaped in certain places, like in a part of the kidney called the “renal medulla.” When this happens, the red blood cells become sticky, stiff, and may block blood flow in the renal medulla. Scientists think this can sometimes damage a gene called INI1 (also known as SMARCB1) in kidney cells, which can lead to RMC. In rare cases, people who do not have any sickle cell conditions can also lose INI1 in the renal medulla, causing a type of RMC called “renal cell carcinoma, unclassified with medullary phenotype” (RCCU-MP).

Aside from having a sickle hemoglobinopathy, there are no known family or environmental risk factors that explain why some people get RMC and others do not. There is also no evidence that family members of someone with RMC have a higher chance of getting it. People with sickle hemoglobinopathies should pay close attention to possible RMC symptoms and see a doctor right away if they notice any. However, there is currently no known way to prevent RMC or test for it in people who do not have symptoms.

RMC is the only kidney cancer associated with sickle cell trait, sickle cell disease, or other blood conditions that cause red blood cells to become sickle-shaped. Even though all sickle blood conditions raise the risk of RMC, most people with RMC have sickle cell trait. Only a few have sickle cell disease or other sickle cell disorders like hemoglobin SC disease or sickle beta thalassemia. This could be because sickle cell trait is much more common than other sickle cell conditions. Pure thalassemias, such as alpha or beta thalassemia, are not linked to RMC. Early studies in people and animals suggest that high-intensity physical exercise in those with sickle cell trait may harm the kidneys and increase the risk of RMC.

All RMC tumors do not have a protein called INI1, also known as SMARCB1, hSNF5, or BAF47. This protein is often missing in other rare cancers, such as malignant rhabdoid tumors (MRT), atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumors (ATRT), and epithelioid sarcomas. INI1 normally acts as a “tumor suppressor,” meaning it helps protect cells from turning into cancer.

RMC most commonly spreads to the lymph nodes in more than 80% of cases. Other areas of the body RMC can spread to include the lungs (67% of cases), liver (27% of cases), and bone (25% of cases).

RMC is often treated with chemotherapy. Many treatments used for other kidney cancers do not work well against RMC. Many of the therapies developed for the most common kidney cancer, known as clear cell kidney cancer, do not work at all against RMC. If a CT, MRI, or PET images show that RMC is only in the kidney and has not spread, doctors might remove the whole kidney and the cancer inside it. If the tumor is large (bigger than 4 cm), doctors may give chemotherapy first to shrink it and then do surgery later—even if the scans do not show any spread. This is because CT and MRI are not perfect and might miss very small tumors in the lymph nodes or other organs. Chemotherapy can help treat those tiny tumors before they grow. Other treatments might include radiation or other special therapies.

Exercise is good for your health, whether you have RMC or not, and even if you have sickle cell trait, sickle cell disease, or another hemoglobinopathy. Animal studies show that doing moderate-intensity exercise may lower the risk of RMC when compared to not exercising at all. However, some early studies suggest that doing long, very hard workouts may harm the kidneys of people with sickle cell trait and raise the risk of RMC. So, exercising at a moderate level may help everyone, but pushing yourself too hard might be harmful. This matches the advice from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention about safe exercise for people with sickle cell trait. Following this advice helps athletes stay safe and get the benefits of exercise.

Moderate-intensity exercise is when your heart rate is between 50% and 70% of your maximum heart rate. To figure out your maximum heart rate, subtract your age from 220. For example, if you are 40, then your maximum heart rate is 180 beats per minute. During moderate-intensity exercise, your breathing speeds up, but you are not out of breath. You might start sweating after 5 to 10 minutes, and you can still talk but not sing.

High-intensity exercise is when your heart rate is 80% or more of your maximum. During high-intensity exercise, you breathe deeply and quickly, start sweating within a few minutes, and can only say a few words before you need to take a breath.

Exercise is not banned for people with sickle cell trait if it is done safely. Athletes and military recruits with sickle cell trait follow simple rules to avoid problems and do well without developing any issues. These rules include staying hydrated by drinking enough water, avoiding a lot of caffeine or stimulants, and not doing many hard, timed drills without enough rest—especially during the first two weeks of a new training session. You should also slow down if you are sick, rest between “sprints” or tough drills, and make sure to take breaks and drink fluids often.

A special thanks to Dr. Pavlos Msaouel at MD Anderson Cancer Center for providing additional information about Renal Medullary Carcinoma.

- Translocation RCC – A rare type of kidney cancer that usually grows slowly. It is caused by a gene called TFE3 being broken apart and rearranged. This type is more common in children and young adults.

- Unclassified RCC: They are very rare and do not easily fit into one of the more common subtypes. They tend to be more aggressive. You may see it written on a pathology report as “NOS”, which stands for “not otherwise specified”.

The term unclassified RCC is used when the cancer does not fit into any of the other major renal cancer subtypes. We are generally seeing that tumors with an unclassified designation behave more aggressively than typical clear cell or papillary renal cancers.

In some studies, there is a higher percentage of females and African American patients with unclassified RCC when compared to “typical” renal cell carcinoma patients.

At this point we do not know of any specific risk factors, although, as mentioned above, there may be a higher risk of developing unclassified renal cell cancers in the African American population.

Unclassified RCC metastases are most common in the lung, lymph nodes, liver, and bone.

At this point in time, the recommended treatment for tumors with unclassified RCC would be a combination of a blood-vessel targeting agent, also referred to as a TKI, plus an immune stimulating agent.

As we gain more knowledge about the different subtypes of renal cell carcinoma, the “unclassified” subtype will become less common. Our goal is to be able to properly classify all renal cell carcinomas into groups where we have specific therapies. We hope this category will eventually cease to exist!

A special thanks to Dr. Eric Jonasch at MD Anderson Cancer Center for providing additional information about Unclassified RCC.

Other types of kidney cancer

Wilms tumor (or nephroblastoma)

Wilms tumors are the most common type of kidney cancer in children. In children, they make up about 5% of all cancers (5 in 100) and 90% of kidney cancers (9 in 10). It most often affects children ages 3 to 4. The most common symptom is a sudden swollen stomach. Learn more from KCA’s Affiliate organization the Wilms Cancer Foundation.

Renal sarcoma

This is a rare type of kidney cancer that starts in the kidney’s blood vessels or connective tissue. There are many subtypes of sarcoma that could affect the kidney, including leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, and malignant rhabdoid tumor. Learn more about sarcomas from the Sarcoma Foundation of America.

Diagnosed with transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) or upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) of the renal pelvis? While this cancer was found in a part of the kidney, it acts like and is treated similar to bladder cancer. Learn more from the Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network.

To learn more about how kidney cancer may be described by a pathologist, see a sample pathology report.

Kidney cancer that has spread to other parts of the body

In advanced kidney cancer, cancer cells can spread to other parts of the body. This is called “metastasis.” The most common sites of metastasis for kidney cancer are the liver, bones, lungs, and brain.

Liver metastasis means cancer from the kidney has spread to the liver.

Symptoms of liver metastasis can include:

- Sweats and fever

- Weight loss

- Swelling of the abdomen (belly)

- Jaundice (yellow skin or eyes)

- Nausea (feeling sick to your stomach) and vomiting (throwing up)

- Confusion

- Dark-colored urine

Bone metastasis is when cancer from the kidney has spread to the bones.

Signs and symptoms of bone metastasis depend on what bones are involved. They can include:

- Bone pain

- Leg or arm weakness

- High levels of calcium in the blood

- Loss of urine or bowel control (unable to control when you pee or poop)

- Broken bones

Liver metastasis means cancer from the kidney has spread to the liver.

Lung metastasis is when cancer from the kidney spreads to the lungs.

- Coughing up blood

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Fluid in the lungs

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

Brain metastasis means cancer from the kidney has spread to the brain.

Symptoms of brain metastasis can include:

- Headaches

- Seizures

- Fatigue (tiredness)

- Nausea (feeling sick to your stomach) and throwing up

- Memory loss

- Depression and mood swings

- Personality and behavior changes

- Changes in thinking, learning, and memory

- Trouble speaking, reading, and writing

- Trouble with attention and concentration – such as confusion, being distracted, and trouble doing more than 1 task

- Trouble with reasoning and judgment

- Cranial nerve symptoms, such as:

- Hearing issues, such as ringing, buzzing, or loss of hearing

- Balance problems

- Loss of muscle control

- Loss of sensation, such as facial numbness or pain

- Trouble swallowing

- Vision problems

KCA has partnered with the American Brain Tumor Association (ABTA).

Kidney Cancer Stages and Grades

After you have been diagnosed with kidney cancer, doctors will try to find out the stage and grade of your cancer. This helps doctors better understand your cancer and guide your treatment.

What is a cancer stage?

A cancer stage describes how much cancer has been found in your body. For example, an early-stage cancer is only in the kidney, while a later stage cancer has spread to other areas of the body.

Knowing your cancer stage is important. It can:

- Help you understand your possible treatment options

- Help you have more informed discussions with your healthcare team

- Help you feel confident that you’re making the right decision about your health and treatment

TNM staging system

The TNM staging system is a widely used system to determine cancer stage. It stands for:

- T – Tumor: The size of your primary (main) tumor and where it is in your kidney.

- N – Nodes: The number of nearby lymph nodes that contain cancer (lymph nodes are tiny bean-shaped organs that are part of your immune system and help your body fight infection).

- Cancer in the lymph nodes is a cause for concern because when there is cancer in the lymph nodes, that cancer is more likely to spread to other organs.

- M – Metastasis: If the cancer has metastasized (spread) to other parts of your body.

When doctors stage your cancer with the TNM system, they will also add numbers after each letter that give more details about your cancer—for example, T1N0MX or T3N1M0. Here’s what the letters and numbers mean:

Primary tumor (T)

- TX: Main tumor cannot be measured.

- T0: Main tumor cannot be found.

- T1, T2, T3, T4: Refers to the size and/or extent of the main tumor. The higher the number after the T, the larger the tumor or the more it has grown into nearby tissues or major veins. T’s may be further divided to give more detail, such as T3a and T3b.

Regional lymph nodes (N)

- NX: Cancer in nearby lymph nodes cannot be measured.

- N0: There is no cancer in nearby lymph nodes.

- N1: Cancer has spread to nearby (regional) lymph nodes.

Distant metastasis (M)

- MX: Metastasis cannot be measured.

- M0: Cancer has not spread to other parts of the body.

- M1: Cancer has spread to other parts of the body.

Based on this information, doctors can give the cancer an overall stage. Kidney cancers are given a stage from 1 – 4:

Stage 1 (I)

Size: Smaller than 7cm (less than the size of a baseball)

What it means:

- The tumor is only in the kidney, is smaller than 7 cm across, and has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or other distant parts of the body.

- TNM staging would be: T1, N0, M0

Stage 2 (II)

Size: Larger than 7 cm

What it means:

- The tumor is only in the kidney, is larger than 7 cm, and has not spread to nearby lymph nodes or other distant parts of the body.

- TNM staging would be: T2, N0, M0

Stage 3 (III)

Size: Any size

Possible options include:

- The tumor has grown outside the kidney into the renal vein or even the vena cava, but not into the adrenal gland. It may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes, but not to other distant parts of the body.

- The tumor is only in the kidney, and the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes but not to other distant parts of the body.

TNM staging could be:

- T1, N1, M0

- T2, N1, M0

- T3, N0, M0

- T3, N1, M0

Stage 4 (IV)

Size: Any size

Possible options include:

- The tumor has grown outside of the kidney and may be in the adrenal gland.

- The tumor may or may not extend beyond the kidney or to nearby lymph nodes. But it has spread to other distant parts of the body.

TNM staging could be:

- T4, Any N, M0

- Any T, Any N, M1

What is a cancer grade?

The grade of a tumor describes how the tumor’s cells appear under a microscope. This can explain how quickly the tumor is likely to grow. Kidney cancers are given a grade from 1 – 4:

- Low Grade (Grades 1 and 2)

The cancer cells are more like normal cells. They grow slowly and are less likely to spread outside of the area where they started growing. - High Grade (Grades 3 and 4)

The cancer cells are less like normal cells. They grow faster and are more likely to spread to other parts of the body.

References:

Information on this page last reviewed: January, 2025

Keep Learning:

The Kidney Cancer Association provides educational literature for anyone impacted by kidney cancer.